Effective negotiation; the lessons of history ?

Those who know me understand that my first love is not corporate finance (!) but history. The two disciplines come together in the arena of negotiation and while the stakes in a deal negotiation could hardly claim to match those in a peace treaty, major industrial dispute or religious conflict, there are many historic examples of good (and bad) negotiations which provide parallels and learning for today’s business negotiators. Please indulge me while I seek to demonstrate this……..

Win/Win

The objective of any negotiation is to get to an agreement which delivers all parties sufficient of what they want for them to agree to the deal. In order to achieve this it is important to understand your counter-parties’ objectives and expectations and to believe that a deal acceptable to you can also deliver for them.

Let’s go right back to c50BC. Cleopatra, Pharoah of Egypt, has fled from Egypt to Syria to escape her brother Ptolemy who also claims the Egyptian throne. Though she is able to raise an army, it is not equal to her brother’s and she needs a much larger fighting force in order to retake the throne. The Roman Empire was already in the ascendancy at this point and following the brutal death of Pompey at the hands of Ptolemy, Julius Caesar set himself up as de facto arbiter between Cleopatra and Ptolemy. Impressed by Cleopatra (and her famous arrival in a carpet), he chose to advocate and support her in the battle for the throne. She in turn provided him with the wealth needed to support his vast Roman army as Julius Caesar turned his attention to Rome. While there is no doubt that the two had the famous love affair depicted by Shakespeare (they had a son), it is also clear that the negotiations between them were founded on sound win/win principles.

A slightly more up to date example of a historic win/win was the Treaty of St Clair Sur Epte in 911AD. In the 10th and 11th Century the Vikings launched regular attacks on North West France. The leader of the Vikings was called Rollo. In 911, King Charles III of West Francia sought to stop the attacks by granting land along the Lower Seine in return for Rollo’s commitment to defend the area from other Viking bands (and that they would convert to Christianity). Rollo’s followers became known as Normans and so successful was the deal they had struck that subsequent Kings of France expanded their territory and a clear Norman identity emerged.

Know when to walk away

It is interesting how easy it is to be sucked into the detail of a negotiation and to lose sight of the overall deal that is being done. While defining your “bottom line” before negotiations begin can be a little hypothetical it is sensible to have a list of red lines that you are not prepared to cross to prevent “deal creep”. It is also sensible to have a (sensible) deadline on getting a deal done to prevent the risk that “deal fatigue” leads to a gradual crumbling of resolve.

I often say to clients that “walking away” is too blunt an instrument to use as a negotiation position and that while obviously it is a tactic open to anyone, you cannot deploy it too often without it looking as though you are crying wolf. There are other, stronger tactics like having a pool of under-bidders ready to step up to the plate if the current deal doesn’t work. Nothing keeps a buyer honest like knowing there are competitors waiting in the wings to do the deal.

One monarch who chose to walk away from a negotiation with huge consequences was Henry VIII. 20 years after succeeding to the throne and 20 years after wedding his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, Henry opened negotiations with the Pope of the time to annul his son-less marriage in 1529. Four years later, frustrated with the pace of discussions and the lack of movement on the part of the head of the Roman church, Henry ceased discussions and divorced his first wife anyway. The excommunication which followed was inevitable. Henry’s objective was absolutely clear and fundamental. He needed a son and no longer believed that the aging Katherine would provide him with one. For the Pope, the red lines were equally clear. There was no ecumenical justification for annulling the marriage and (more to the point), Katherine was a close relation of the Holy Roman Emperor. That said, it is difficult to believe that the Pope would have believed that his English “Defender of the Faith” would be willing to walk away. What is clear is that the positions of both parties hardened over time as their emotional commitment to their negotiating positions and their anger with the other side intensified. Certainly anyone who has been involved in a protracted deal negotiation will have some sympathy with Henry’s decision to walk away from the table after four long years !

Back Channeling

One of the best reasons for using an adviser to negotiate a deal on your behalf is that they are emotionally removed from the business and the deal. I have written before about how difficult it can be not to take offence during a due diligence process at perceived criticism and not to get frustrated with “stupid” or “irrelevant” questions. An adviser can balance challenge with a lack of emotion to deliver the answers that are needed without ending up seeing a red mist…..

The other mechanism that a good adviser will sometimes use is the opportunity to circumvent or diffuse a potential impasse in a negotiation by means of gently exploring the other party’s position behind the scenes. Making it completely clear that you don’t have the permission of your client and that you are simply exploring how a position might be unlocked can help move two entrenched parties closer together without any loss of face. A little give from one side can often unlock a completely different flavour of discussion.

Nelson Mandela is often cited as a champion negotiator for many excellent reasons. One of the tactics he used to help reach an agreement between the ANC and the South African Government was to break through the impasse in formal discussions and through the deep antipathy between the parties by back channeling. When he wrote to the South African Minister of Justice offering secret meetings he wasn’t officially mandated by the ANC to negotiate on their behalf but by so doing he was able to unlock a more fruitful discussion. His acknowledgement that “Hating clouds the mind” would be a useful reminder in some of the more testy late stage negotiations I have been party to.

John F Kennedy of course used a similar tactic during the Cuba Crisis, choosing to ignore a particularly belligerent message from Kruschev and choosing instead to respond to an earlier and more conciliatory one. The crisis was solved by producing a solution which gave Russia something it needed (if only to save face) in return for turning the ships around.

Retaining a hold on reality

When we take a business to market, naturally we present the business in the best possible light. We identify all of its positives and communicate all of its potential. The business looks as shiny and beautiful as it can be made to look consistent with the truth. In the same vein, we present the numbers on an adjusted and normalized basis so as to get to the highest valuation possible (consistent with the truth).

We are always careful to remind a client that the purpose of the information memorandum is to get to the best possible price and that there is every likelihood that during the process of due diligence, as things potentially come out of the woodwork and/or if the business fails to perform in line with the numbers presented, that some degree of price adjustment is a risk.

Whatever warnings are issued, clients tend to focus on the Information Memorandum as a source of truth and to be offended, annoyed if the buyer/investor challenges it as they go through due diligence. Keeping tight hold on reality and remembering the line between that and deal PR is important to achieving a sensible and fair outcome.

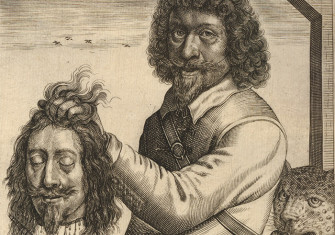

One English monarch who lost a grip on reality and paid the ultimate price for it was King Charles 1. His two predecessors, James 1 and Elizabeth 1 had both played a masterful game with parliament, using the vocabulary of divine right and monarchical supremacy but in practical terms acknowledging the rights of parliament to control the grant of funds to the throne. Charles believed in the divine right of Kings to the point where he would not acknowledge the right of Parliament to limit his power at all, refusing to even call parliament between 1629 and 1640. In losing this perspective and believing the royal PR of the previous 100 years Charles put himself at direct loggerheads with his parliamentary class and when in 1640 he had no choice but to recall them to ask for money to fight a war with the Scots, his continued refusal to meet them halfway ultimately resulted in the English Civil War and, in 1649, with his execution !

Conclusion

Negotiation, like history, is all about people. Good outcomes are based on fairness, acknowledgement of objectives, a win/win approach, honesty, trust and a bit of psychology. When positions become entrenched, tempers get frayed and reality goes unacknowledged, then things get difficult.

Fortunately, whereas in many of the historical examples cited, the ultimate recourse was or could have been to physical violence, the worst that can happen in a deal is intense irritation and a breakdown in relationships !

by Wendy Hart

Wendy Hart

Partner

Why HMT

Latest News